Efficient Technical Writing Processes for API Documentation

The time of APIs being a hot new trend is long gone, and now the vast majority of tech companies are familiar with the process of building and maintaining APIs. The API First movement got teams putting more focus on their public APIs, “dog-fooding” them (using them internally to find kinks and quirks) and throwing huge effort into making documentation as simple as possible for onboarding and integration, but still “partner” or “integration” APIs are often being left behind.

These secondary APIs are no less important, in fact they may well be crucial to the business, but far too often it’s left as a spreadsheet or Google Doc that gets outdated as soon as it has been shared, and trying to improve the content or make sure all the endpoints are covered is a nightmarish job for tech writers.

So what’s the best approach to efficiently create thorough API documentation?

Who Should Document APIs? #

There’s no one role that should be entirely responsible for documenting an API. It will be developed by the engineering team, but they are not usually the best folks to write documentation. Not just because it takes a lot of skill and experience to put yourselves in the shoes of an end user who has no experience, but they could also be working on other features instead of trying to get them writing pages and pages of Markdown.

Who else is there? An API may well be built according to requirements from API Product Manager, but that concept is so new there may not be anyone from product involved at all, other than somebody from business saying “can you integrate with company X somehow”?

Technical Writers are often expected to pretty much all of the work, but generating high quality documentation from thin air is incredibly difficult, especially if things are changing with the API rapidly.

There’s a middle ground to be found where everyone can leverage their very particular set of skills.

Getting OpenAPI Involved Early #

The sensible approach is to get tech writers involved earlier on, and using OpenAPI as a central source of truth, the engineers, product, and tech writers can all work around that format, making sure that the fundamentals are correct: endpoints, headers, request/response bodies, validation rules, etc. then the technical writers can plug in their excellent written word into the human-facing parts of the API description to help power amazing API reference documentation tools.

How exactly do you go about doing this?

Option 1.) API Design First #

Once you’ve finished whatever white-boarding and requirements gathering from your planning sessions, engineers and product people can start designing the API you’re thinking of building, whether that is using OpenAPI Editors, or just opening a text editor and writing OpenAPI by hand.

Another popular new option is to see how far you can get with things like ChatGPT or GitHub Copilot, who can turn a series of prompts like the following into a half-decent OpenAPI starting point.

Write an OpenAPI description for an API game of tic tac toe where multiple games can be played at once, with endpoints for starting a new game, making a move, and seeing the status of the game. Use OAuth 2 authentication and add errors using the RFC 7807 format.

However the editing is done, if the code and OpenAPI are living in the same Git repo, you can use the OpenAPI to power the code, then the technical writers can keep chipping in extra descriptions and improving the situation whilst the engineers keep adding new endpoints and properties over time.

We’ve written some guides on how to leverage the design-first workflow in Laravel PHP and Ruby on Rails, but there are great tools out there to help you with most popular languages/frameworks.

Option 2.) Use a OpenAPI-aware framework #

Tech writers don’t always have a say in the API design/development workflow, but if you do, and people aren’t interested in API Design First, try to recommend your engineers using OpenAPI-aware web application frameworks: it’ll make all your lives easier.

Using these modern OpenAPI-aware frameworks, the engineering team can start to build the API, and whenever the first prototype or beta is ready they can export the OpenAPI with a single command and it’ll be right there for you to pick up and extend.

# Using Huma you can export OpenAPI from your code

go run . openapi > openapi.yaml

This example from the Go framework Huma is just one modern OpenAPI-aware framework that can do this, but you can also consider API Platform for PHP, or FastAPI if Python is more your cup of tea.

Most of these tools will export OpenAPI right over the top of the previous OpenAPI, overriding any previous changes. This is not ideal, and it’s likely these tools will eventually start offering “merge” functionality, but in the meantime how can you add valuable content to OpenAPI contributions without having it vanish on the next build?

Modifying OpenAPI Descriptions without losing your changes #

Regardless of how your OpenAPI is being changed, there are times when you might want to change some things without wanting to (or being able to) change the original. Whether that’s the code-first approach exporting OpenAPI, or some engineering teams using API Design First might produce it somewhere the technical writers cannot access, there will be times you need to modify OpenAPI to improve it for various audiences.

A working group at the OpenAPI Initiative have released a new concept called “Overlays”. This is separate specification but compatible with OpenAPI, and while it’s still experimental it can be considered stable enough for people to start using.

# overlays.yaml

overlay: 1.0.0

info:

title: Overlay to customise API for Protect Earth

version: 0.0.1

actions:

- target: '$.info.description'

description: Provide a better introduction for our end users than this techno babble.

update: >-

Protect Earth's Tree Tracker API will let you see what we've been planting and restoring all

around the UK, and help support our work by directly funding the trees we plant or the sites

we restore.

To get involved [contact us and ask for an access token](https://protect.earth/contact) then

[check out the API documentation](https://protect.earth/api).

Using OpenAPI Overlays you can effectively “patch” an OpenAPI description, pointing to parts of the original document with JSONPath, then adding or updating your content in. You can add as many actions to these overlays as you like, or make multiple overlays.

To work with Overlays you’ll need a tool that understands them, and that’s not all OpenAPI tools as the concept is still very new. Regardless of what API documentation tool you are using, you can use the Bump CLI to apply these overlays, and this will produce a new user-facing document.

$ bump overlay openapi.yaml overlays.yaml > openapi.public.yaml

You can run these commands in continuous integration, and whatever you would have done with the original you can now do with the new openapi.public.yaml (or whatever you decide to name it).

Here’s part of a GitHub Action used to deploy overlay-based improved documentation.

name: Deploy documentation

on:

push:

branches:

- main

jobs:

deploy-doc:

name: Deploy API doc on Bump.sh

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Apply overlay to API document

run: |

npx bump-cli overlay api/openapi.bundle.yaml api/overlays.yaml > api/openapi.public.yaml

- name: Deploy API documentation

uses: bump-sh/github-action@v1

with:

doc: partner-api

token: ${{secrets.BUMP_TOKEN}}

file: api/openapi.public.yaml

Learn more about Overlays and using them within Bump.sh.

Adding more context as Technical Writers #

Whether you’re using overlays or contributing to the original OpenAPI, what exactly should you be focusing on?

Engineers will often focus very much on the “how”, but leave out some of the “why”, or really explain the “what”, so you can add this in.

Tags #

Tags are a really useful place to explain some of the concepts being used. For example an Order and an Organization might seem fairly obvious what it is to the engineers working on it, but you could add context to them.

Here’s an example of an overlay you could use to expand the tag. Descriptions with a whole bunch of Markdown, and links to other resources.

# overlays.yaml

overlay: 1.0.0

info:

title: Overlay to customise API for Protect Earth

version: 0.0.1

actions:

- target: '$.tags[?(@.name=="Order")]'

description: Provide more information for Order tag.

update:

description: >

The Order resource represents a single order for trees, which can be fulfilled by one or more

deliveries. Orders are created by the [Protect Earth team](https://protect.earth/contact) and

are used to track the progress of your order from creation to delivery.

- target: '$.tags[?(@.name=="Organization")]'

description: Provide more information for Organization tag.

update:

description: >

The Organization resource represents a single organization, which can be a charity, business,

or other entity. Organizations are created by the [Protect Earth team](https://protect.earth/contact)

and are connected to each of your Orders.

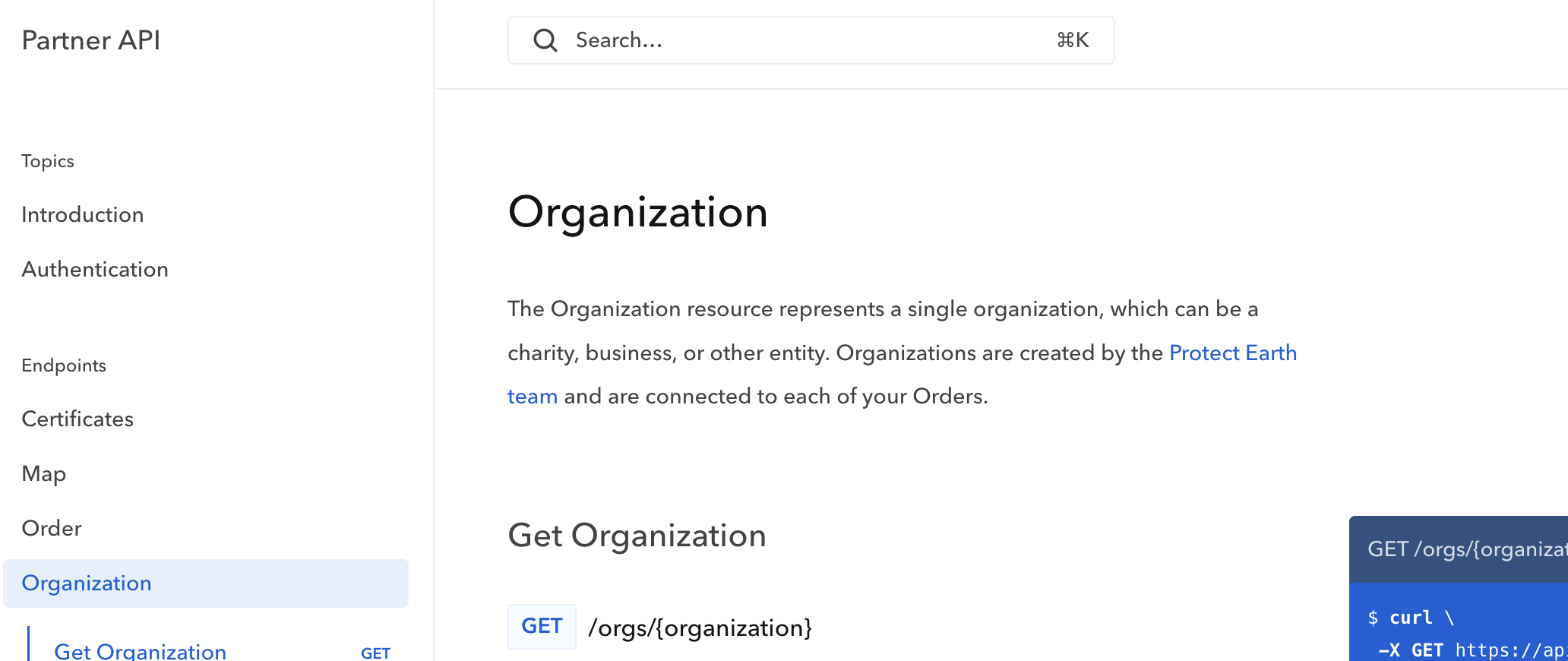

These descriptions (which can be much longer and full of even more Markdown) will then show up in API Documentation, pride of place, ready to explain the concepts to the user before they get stuck into what specific endpoints are about.

Here’s the tag description rendered in Bump.sh.

Introductory Topics #

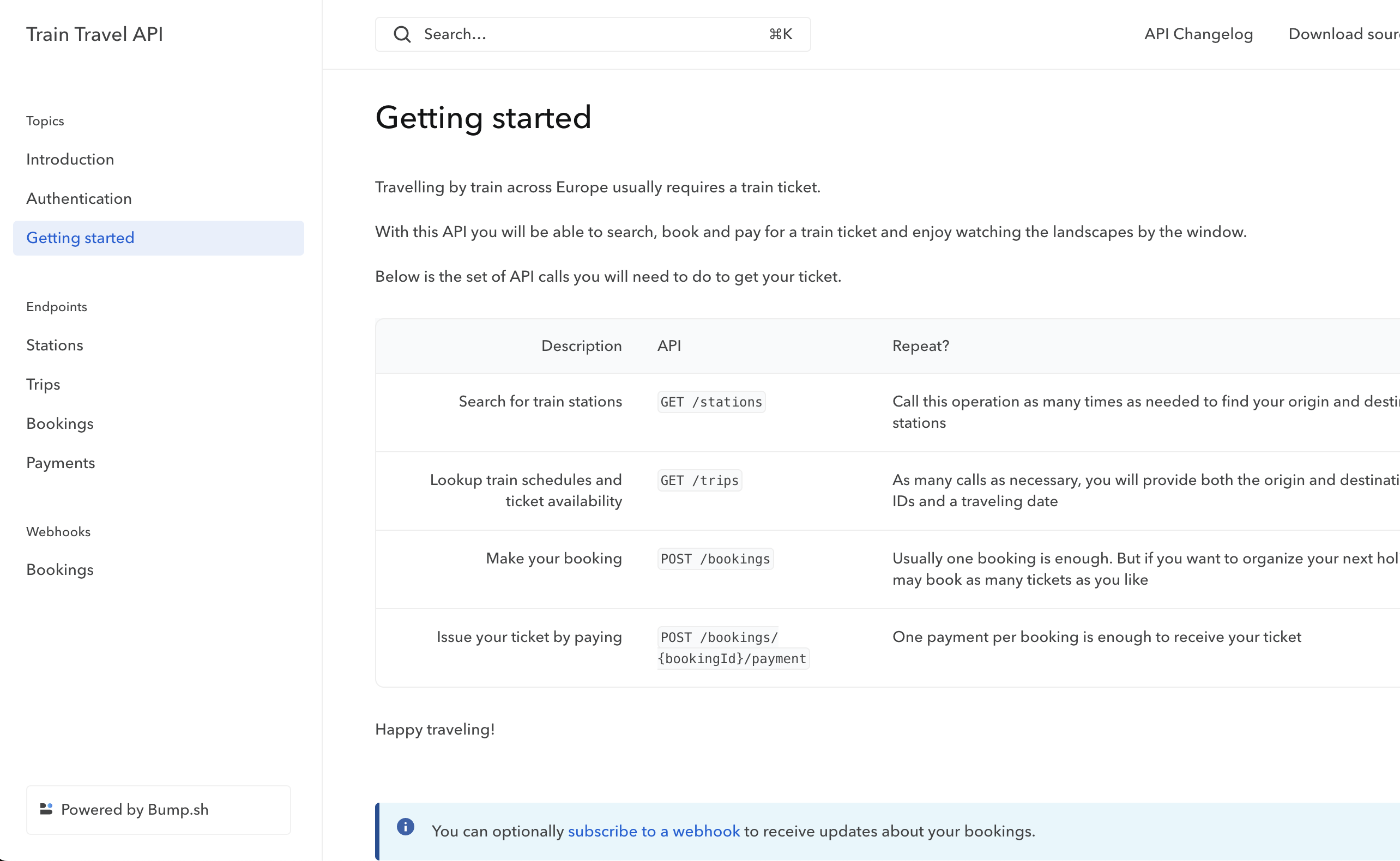

There are quite a few handy “vendor extensions” around which you can add more power to any tooling that knows how to respond to them. One particularly useful one is x-topics, which allows tech writers (or anyone else messing with this sort of work known as “doc ops” or “spec ops”) to expand on just the API Reference Documentation, and start introducing end-users to other guides and content.

openapi: 3.1.0

x-topics:

- title: Getting started

content:

$ref: ./docs/getting-started.md

In Bump.sh this will create a new navigation entry, and insert the Markdown content from the reference guide right into the main documentation.

Whether you inject x-topics with Overlays or directly into OpenAPI in the source code, the result is the same.

Code Samples #

There’s countless other improvements you can make to the source OpenAPI given to you by the engineering teams who have other things to be worrying about, like adding client-side code samples with x-codeSamples.

paths:

/users:

get:

summary: Retrieve a user

operationId: getUserPath

responses: [...]

parameters: [...]

x-codeSamples:

- lang: ruby

label: Ruby library

source: |

require "http"

request = HTTP

.basic_auth(:user => "name", :pass => "password")

.headers(:accept => "application/json")

response = request.get("https://api.example.com/v1/users")

if response.status.success?

# Work with the response.body

else

# Handle error cases

end

External Documentation #

You could add externalDocs to point them to tutorials hosted elsewhere.

tags:

- name: Stations

description: Train Stations all over Europe, using a bunch of standards defined elsewhere.

externalDocs:

url: https://train-travel.example.com/docs/stations

Filter out anything that shouldn’t be there, like beta endpoints that are not ready for public use. There’s a few ways to do this.

Bump.sh users can do this with the x-beta property:

paths:

/diffs:

post:

description: Create a diff between any two given API definitions

x-beta: true # Beta flag at the operation level

requestBody:

description: The diff creation request object

content:

application/json:

schema:

type: object

x-beta: true # Beta flag at the top-level schema object

properties:

url:

type: string

format: uri

x-beta: true # Beta flag at the object property level

description: |

**Required** if `definition` is not present.

Current definition URL. It should be accessible through HTTP by Bump.sh servers.

Or you can filter them out with overlays:

overlay: 1.0.0

info:

title: Remove beta flags

version: 0.0.1

actions:

- target: "$..[?(@['x-beta'] == true)]^"

description: Remove anything beta

remove: true

Learn more about working with JSONPath to write powerful targets for your overlays using our guide How to work with JSONPath.

Consolidate multiple APIs and services to one Hub #

Once you’ve created API Reference Documentation for a single API, why stop there? If you’ve got multiple APIs you can start to pull them all together into one place, so people don’t have to go rummaging around to find different bits of documentation.

Different teams often end up implementing their own documentation in different ways, even when all using OpenAPI. Some bake it into the API and make it available on an endpoint like https://example.com/api/docs which is pretty handy for the developers, but that might be hidden behind various firewalls, VPNs, and authentication. Some teams export the docs as HTML and pop it into a /docs folder in the repo, but that locks the documentation away behind source control logins, and even with a GitHub pages setup thats going to look very different from your other docs.

Pulling all of your various APIs and disparate documentation hosting sources together into one place is usually known as creating an API Catalogue, and there are plenty of ways to do it. You can build it all yourself, or you can use an existing solution, like Hubs in Bump.sh.

You can pull in from multiple sources, and use bump deploy to push local files or even read URLs, and now you can run all the overlays you want in the process, to make it look brilliant and read excellently.