Primitive Concepts of Git

Git supports effective collaboration among large groups of people. Using drawings and concrete examples, you will learn how a few simple concepts can be used to support sophisticated social interactions. You will learn enough of Git to decide whether you want Git in your toolbox, or perhaps why others in a collaborative project insist on using Git. And you will learn without touching a command line.

Git was born to support Linux, a large open source project developed by many people across the World. You could hardly ask for a more inauspicious start:

Initial revision of “git”, the information manager from hell. — Linus Torvalds, 2005

However, after satisfying the complex needs of Linux developers, Git adoption grew to the point when it is now the first choice for most people.

Files and trees #

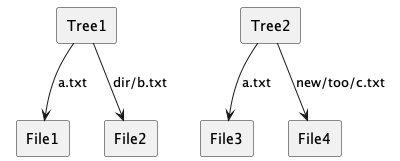

First of all, Git stores files organized in a hierarchical tree, just like your typical file system does. In particular, Git stores the contents of files and their pathnames. Going beyond what a filesystem usually does, Git can store multiple trees.

Here is an example of two trees with four files.

Commits #

Commits give meaning to the multiple trees stored in Git. Each commit remembers that, at some date and time, someone (the author) asked Git to remember a specific tree, with a message that typically states a reason.

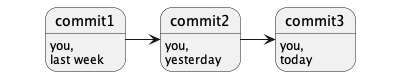

In practice, people store multiple trees into Git because the trees are related to each other. For that purpose, Git relates each commit with one or more previous commits, called the parents.

For example, you may want to remember the evolution of a tree over time, so that you can go back in time and recover previous revisions of files. Each commit would indicate the previous one as parent, creating a sequence of points in time:

Merge commits #

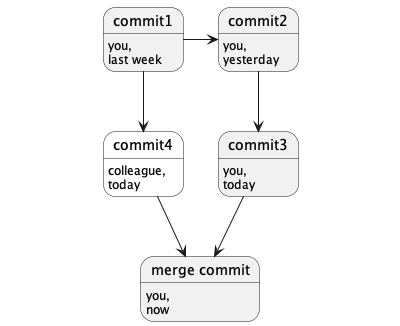

Commits get more interesting once you notice that Git can remember commits from multiple authors. Commit parents support collaboration among authors.

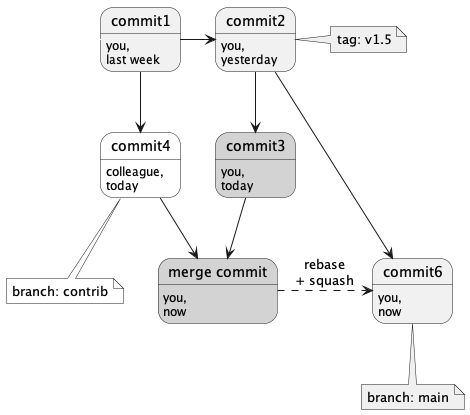

Picking up the previous example, imagine that a colleague needed to work in the same tree of files.

-

She picked up your work from last week, did her work, and committed her work today as “commit4”, as shown below.

-

During the same time, you also continued to work, and committed your changes yesterday and today.

Finally, you ask Git to combine your work with the work of your colleague. Git creates a merge commit with two parents that combines the changes of both of you, as follows:

-

If you and your colleague worked in different files, Git automatically takes the latest version of each file.

-

If you and your colleague worked in different parts of the same text file, Git automatically combines the changes into a single file.

-

Otherwise, you have conflicting changes. You will have look at both revisions of the file and figure out what the final result should be, before Git can complete the merge.

Note how Git remembers that work diverged and later converged, including the before, the after, the between, who did what, and who merged the work.

Tags and branches #

In the last section, we just told a little story of five commits, from commit1 to merge commit. A real project will accumulate many such stories, as several persons contribute their individual and collaborative work. For example, the Linux Kernel (the project that originated the development of Git) has accumulated over one million commits since 2005.

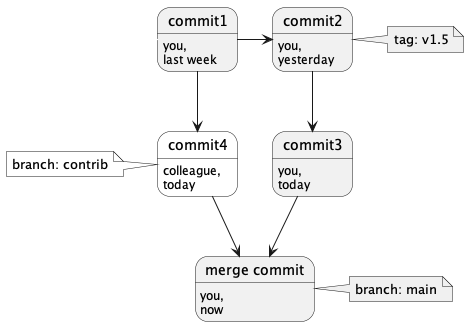

To navigate the avalanche of commits, Git has two ways to give names to commits:

-

Tags name an event in time. For example, the tag “v1.5” might name the tree that was shipped to customers last week.

-

Branches name an effort, and point to the tip of a sequence of commits. Branches answer the question “where is the latest work on x?” By convention, the branch “master” or “main” has the latest consolidated work.

Building on our example:

- Tag “v1.5” remembers commit2 for posterity.

- Branch “contrib” currently points to commit4, the work of your colleague.

- Branch “main” currently points to the latest work, the merge commit.

Last week, branch “main” pointed to commit1. As you delivered work during the week, branch main pointed to commit2, commit3 and, finally, the merge commit.

When your colleague needed to start her work last week, she did not have to ask you for the latest release: she just picked up the files from branch main (commit1 at the time). Today, she delivered her work in the separate branch “contrib” and asked you to integrate her work into main.

Rebase and squash #

When a larger number of people collaborate over time on Git, a large number of branches and merges can make history difficult to understand. For example, a feature may have hesitated back and forth between alternatives and failures, with the Git history showing every little change, every little mistake.

Git has several ways to copy changes between branches, or to consolidate changes into a single commit. While the variations are beyond the scope of this article, we will show how you might consolidate several related commits into a single commit.

For our example, you could use the Git operation “rebase” with the option “squash” to consolidate commit3, commit4, and the merge commit into a new commit6, as shown below.

The result is a commit that has the same tree as the merge commit, but that lost the memory of commit3, commit4, and the merge commit. This simplified history may be useful or even required, but it also has several consequences:

-

Git remembers you as the sole author of commit6. The contribution of your colleague is no longer distinguished from your own work, although the commit message may still mention her contribution.

-

Branch “main” now points to commit6. The commit3 and the merge commit became orphans, in the sense that no branch and no tag knows about them. Git eventually removes these “unused” commits, possibly forgetting important work.

-

If your colleague continues to work on branch “contrib”, the branch “main” no longer remembers that she already delivered some of the work. You may get surprising behavior when you try to merge her work again.

Work tree #

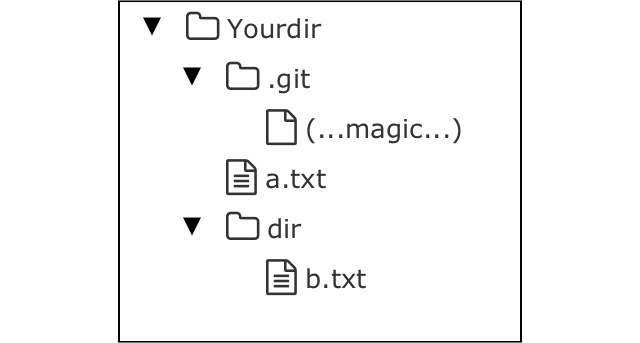

To start working with Git, you initialize a Git repository within a directory. The repository has a copy of the files you are working on, plus a special “.git” directory that stores your multiple trees, files, commits, tags, and branches.

The example below has two files, “a.txt” and “dir/b.txt”, together with the magical “.git” directory.

Usually you work on a branch as follows:

-

You “check out” a branch to retrieve the files associated with the latest commit of the branch, replacing the files in your directory.

-

You work on your files, perhaps changing, adding, and deleting files.

-

You commit some or all of your changes into Git, adding them to the current branch. Git tools show you a list of changes, and you decide whether to commit all changes, or only some of them.

Clones and remote repositories #

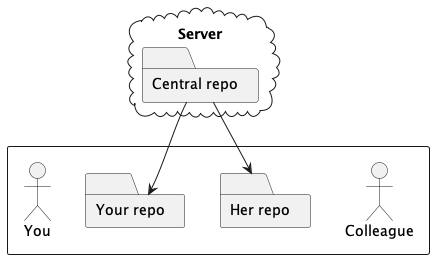

If Git is just managing directories in your computer, how do you collaborate with others? Git is a distributed version control system, meaning that each person has its own local repository, but Git can synchronize changes between a local branch and a remote branch at another repository. You can either pull commits from others, or push your commits to others.

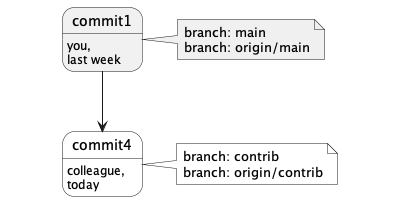

For example, how can your colleague work on her computer and then deliver her changes to you? Last week, when your colleague needed to work on your files, your repository had just the branch “main” with commit1. To work on her own computer, your colleague did the following:

-

She “cloned” your repository to a directory in her computer. Git copied your branches and commits, and automatically checked out the latest files from the “main” branch into her working tree.

-

She worked on the files on her working tree until she was ready to share her work with you. To avoid any chance of conflict, she committed her work to a new branch “contrib”.

-

She “pushed” her new branch “contrib” to your repository, for you to get a copy of her work.

This is what her repository looked like. Note that she has no idea that you delivered commit2 and commit3, although she could have pulled changes to the branch “main” to get those commits and synchronize her branch “main” with your work.

To coordinate the work of multiple people, one of the repositories is designated the central one, and everyone clones, pulls, and pushes to that repository. This central repository is typically hosted on a server and, often, on a platform such as GitHub or GitLab.

Pull requests #

You probably did not have any problem with your colleague pushing her work to your repository. But she might as well have pushed changes to your “main” branch, and you might have sent those changes to a customer without reviewing her work.

Git pull requests enable collaboration between people that do not blindly trust each other. Your colleague would send you a request to merge her work into your branch “main”, and you would have the final word on accepting her changes. For example, you might insist she addressed some concerns before you accepted her work.

Platforms such as GitHub and GitLab further support sophisticated collaboration among many people. Besides hosting central Git repositories, these platforms support pull requests with nice Web-based or native interfaces, and fine-grain control over who can pull, push, or merge. They also add the ability for people to argue over a merge request, line-by-line if needed.

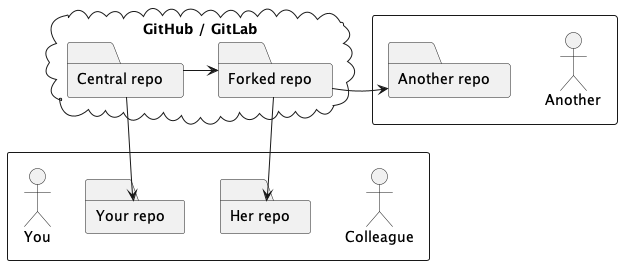

For example, suppose that your colleague needed to work with another person working remotely, perhaps from a different organization. They needed to collaborate over a longer period, exchanging work back and forth, until they finally submitted the work for your review in the form of a pull request.

Platforms such as GitHub or GitLab support that work by setting up a hosted clone of the central repository, which is commonly called a fork. Your colleague would collaborate with the other person over that fork, possibly using several branches, possibly using mutual pull requests.

What have we learned so far? #

Here are the major concepts that you have learned in this article:

-

Files in a tree: Store revisions of a hierarchy of files over time.

-

Commits: Remember when, why, and who asked Git to store each revision.

-

Parents: Track history automatically, either when work diverges (new branch) or when work converges (merge).

-

Tags: Name a specific revision, typically a delivery or a release.

-

Branches: Track work streams. Remote branches synchronize work across repositories.

-

Working directory: The directory where you work, while Git remembers your previous work in the “.git” directory (the repository).

-

Pull request: Polite request to deliver work to another repository. Platforms such as GitHub and GitLab enforce policies and support conversation over changes in pull requests.

What next? #

These concepts should be enough for you to figure out whether Git is a good solution for you. To actually use Git, you will need to adopt a tool and learn its peculiarities. And that’s when the journey gets interesting.

At its heart, Git is a simple solution that supports complex behaviors. Although all graphical Git tools support the basic functionality, they differ in advanced functionality, and they can favor different ways of working. For example, some graphical tools emphasize the current branch, while other graphical tools show all branches. That’s why most Git guides adopt the command line as a neutral approach.

While the command line is available in every system and can be extremely effective, a graphical Git tool helps visualize the state of files in the working directory, visualize the history of commits in the repository, and understand what changes you are about to commit. I can vouch for two open source tools:

-

TortoiseGit, a Windows shell extension that excels at showing changes in the working directory, and that supports advanced needs as well. I have used TortoiseGit professionally, and I have successfully taught non-technical people to use this tool.

-

GitX, a MacOS application devoid of advanced functionality, but enough for daily use. I use GitX for my personal repositories.

Whatever the tool you choose, including the command line, two habits will help you collaborate with others over Git:

-

Always review your changes before you commit. This practice will stop you from confusing your colleagues by committing spurious files or by mixing unrelated work in the same commit.

-

If anything feels off with your Git repository, stop and ask for help before you get in trouble. Experts have learned to respect Git, in the same way you would respect a sharp tool. Experts know the corner cases that can trap the unwary. I learned both from colleagues and from the Internet, before I also helped colleagues stay out of trouble. Beware of rebases and merge conflicts.

Git is one of those tools that takes minutes to learn and a lifetime to master.

-

The Git-scm home is a good place to download a Git client and explore the official documentation.

-

The freely available book Pro Git by Scott Chacon and Ben Straub was instrumental in my journey to relative Git mastery, and was also an irreplaceable reference for this article.

To Git or not to Git, that is your question now. I wish you a nice journey.